Feature: Little Big Man – An Interview With Phil Little

Mike Kennedy

Words: Mike Kennedy

[Guest Writer – Welsh Connections/SWND Records, Director | Oystermouth Radio – Presenter]

The word ‘legend’ is used too freely these days but as a drummer there are a few drummers that I would class in that category.

There’s Steve Gadd, Jim Keltner, Billy Cobham and Ringo – but one drummer in particular who trained with the jazz greats and formed The Flying Pigs with Man’s Micky Jones and Mick Hawksworth from Ten Years Later deserves a special mention too.

I caught up with Phil Little ahead of the release of his new album ‘Dial S For Space’ recently to talk about his career.

To start, I asked Phil about the Pink Floyd influences on his new album and why he’s such a fan:

Phil: “It was in 1967, when I was aged 14, that I first saw Pink Floyd at the Liverpool Empire Theatre. They were on just before Jimi Hendrix and it was the very first gig that Syd Barrett didn’t show up for.

It was only a couple of years ago that I found out that Dave O’List, from The Nice, stood in on guitar that night, wearing a hat to disguise himself. I can remember that big hat and him with his back to the audience and at that time I wasn’t really aware who Syd Barrett was. I had already bought ‘Arnold Layne’ after hearing it once on the radio.

So, that night, Pink Floyd got by with ‘Arnold Layne’ and ‘Interstellar Overdrive’ without the overdrive. It was something about the sound that Rick Wright got from the Farfisa organ that attracted me and there’s an effect that you can hear clearly at the beginning of ‘Astronomy Domine’ that really did sound futuristic in the 1960’s. Their clever use of riffs and unusual sound effects definitely made them sound new and different at that time.

In 2017 my daughter took me to see The Pink Floyd exhibition at the V&A Museum, which was fantastic and sold-out. There I got the chance to have a close-up look at all the equipment including the early keyboard setup with effects units. The next day I was experimenting with digital versions of the effects I had seen and was enthused by the results. Around the same time, I was listening to ‘Piper At The Gates Of Dawn’ a lot and being generally impressed by the genius of Syd Barrett.

Barry Jones is also a fan of this album and, incidentally, was in a psychedelic band in London called The Purple Umbrella, so he was enthusiastic about doing something psychedelic in a live setting. If you listen, there’s also a big Man influence in evidence on the new album. I first heard them in 1971, when I lived in a psychedelic house with five other chaps, one of whom brought home ‘7 Inches Of Plastic’ one day, and that became one of the albums we listened to a lot.

By the time I was settled in London in 1972, ‘Greasy Truckers [Party]’ came out and I bought that straight away. So impressed was I with the long side by Man, I used to play it all the time and practice with the pad along to it in my Tooting bedsitter, wondering how a band got so tight. It was the riffing again that held my attention. Nothing beats tight riffing.

Terry Williams is the ultimate rock drummer, and his timekeeping is so spot on it proved to be an excellent substitute for a metronome. Melody Maker actually called him Terry ‘Metronome’ Williams in one edition. Man albums like ‘Be Good To Yourself’, ‘Back Into The Future’ and ‘Slow Motion’ were constantly on our turntable during the seventies.

Years later I would be playing with Micky Jones, one of, if not the, premier British psychedelic musician. After he moved out of London, Micky would pick me up and stay at ours after Flying Pigs gigs, so we had many a night chewing the fat, unwinding and getting wrecked. A lot of the musical excursions we took with the Flying Pigs were lengthy and often unscheduled, and it is partly the danger of not knowing what is coming next that excites both the musicians and audiences alike.

Man used to make their jams sound [like] part of the arrangement and that is neat. They were also really good at writing songs in different structures [other than] pop songs and were expert at constructing arrangements that provided opportunities to launch into those vital improvisations, which we all anticipated.

In my mid-teens, a conversation with one of my music-appreciating friends might have gone:

‘I went to see so-and-so in Liverpool.’

‘Did they do a jam?’

‘Yeah.’

‘How long did it go on for?’

‘Twenty minutes.’

‘Brilliant!’.

In 1992, I promoted a few Man gigs in Hastings and St Leonards. The first time they played at The Yorkshire Grey, the pub was heaving and people had come from all over the South East to see them. They played all the hits and were absolutely terrific and blew the roof off the place, which sold out of beer. On that occasion the band stayed in my Light From Darkness Studios, which was in the basement of a huge place called The Observer Building in Hastings.

The band liked it there because they could have a play in the studio where my drums were set up. As an enormous Gentle Giant fan and having promoted one of their early gigs in Widnes in 1971, I was rather chuffed to have Gentle Giant’s drummer John Weathers playing my vintage Ludwig kit, purchased from John Ham’s in Swansea. In fact, I loaned John my bass drum pedal for the gig.

Phil Little and Mick Hawksworth

The new album [‘Dial S For Space’] is based on a story about an astronaut sent out to find a new home for humans. In the ‘60s and ‘70s, I’m sure a lot of people had the idea that was the future for the human race. It doesn’t take a high IQ to quickly work out that if you keep mining metals and oil then eventually all of the Earth’s resources will have been used up.

So, why fashion a way of life that is almost totally dependent on them? It is plain to see that we have not been well-represented by our leaders for hundreds of years. In such a case, you might think the only way for the human race to survive is to find another planet and start again, but any potential candidate for a host planet is so far away that it could take a thousand years to reach.

They have been discussing how man might survive and accomplish such a mission for years, and there are plenty of fictional films touching on the subject. Then there are the moral issues of how could a ‘state’ send a man or woman off on such a mission with minimal chance of survival? Also, there are the mental health issues of somebody surviving the isolation and loneliness.

That solution is made difficult now because, notwithstanding the science, there are so many divisions between people and nations and so many people just don’t get it, in the same way they don’t get wearing masks or voting for right-wing politicians when you haven’t two pennies to rub together. So, an interstellar escape for the human race would depend on us all working together and facing up to some humbling realities. Not impossible but requiring much change in order to progress.

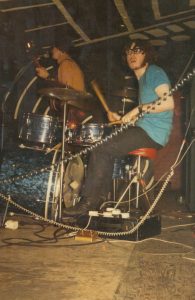

Phil performing in Liverpool, c. 1969

Since I began imagining this record two or three years ago, it wasn’t really influenced by the COVID crisis. But when I was recording the vocals for songs like ‘Fear And Me’ and ‘Into The Ice’, I began to realise the close parallel between the astronaut’s situation of ‘no return’ and our own present dilemma where many people have an uncertain future giving rise to a variety of fears and emotions. And not much help in dealing with them.

Also, some of us experience the apprehension of undergoing an operation or treatment and perhaps going under an anaesthetic. When I had the first eye operation, I had a general anaesthetic and it was terrifying. They ask you to count down from ten, and I introduced that apprehension into the lyrics of ‘Into The Ice’.

When I’m writing, a blank canvas always appeals to me and mostly I started by trying to come up with riffs and chord progressions that were within my limited technique. Unless it’s a percussion track, the drums are nearly always finished last, which is the opposite way round to how you would record a band.

One of the main things I wanted to capture were these spacey breakdowns where you just float off on a bed of sounds. One of the first things I did was wind up all the effects on my POD guitar FX processor and just go crazy. The sound of the Farfisa Organs is distinctive, and I used it to imitate the effects Rick Wright employed on the early Floyd recordings.

Having little confidence in my singing, a lot of my music is instrumental and at the last rehearsal we had, Barry Jones said: “We need songs!” So I attempted to make some songs. The first set of words was for ‘Just A Speck In The Distance’ and afterwards I thought about what might happen after launching into space.

One of the characteristics of psychedelic albums was ‘whimsy’ songs and I had learnt to sing and play ‘The Gnome’, so I wanted to include my own whimsy song. With ‘Fear And Me’, I had found a nice chord progression on the Internet and almost as soon as I played it the first two lines presented themselves, and then the rest just sort of fell out very quickly. You hear about it but that isn’t what usually happens with me.

Also, I wanted to experiment with the old mechanical methods of producing sounds and effects, such as the bottleneck on the guitar, or the plectrum scraped down the length of a string with lots of delay and reverb. In the first track, ‘Origins’ I recorded my own cymbals upside down, attempting to capture the rich tones.

I tried, without success, to get two tape machines so I could have a go at looping lengths of tape around furniture etc. in the manner of Pink Floyd and Ron Geesin. Micky Jones was a master of delay and his Echoplex was always featured heavily in his sound with The Flying Pigs – at least up until the disaster at the Stonehenge Festival in 1982, when somebody accidentally tripped on the power lead and pulled the delay unit onto the stage just as we were about to start the set.

Of course, it was broken and our performance severely handicapped. As soon as possible afterwards, Micky got hold of a delay pedal and we continued with that. Somehow the vintage Echoplex with its mechanical tape loop was more atmospheric than the electronic pedal. After decades of misuse, Micky’s Echoplex has been renovated by Micky’s son George who now uses it again with Son Of Man.

On the new album, Barry Jones played bass guitar on four of the main tracks and supported me throughout the project. Currently, I am recording some percussion for his new record. Barry’s music comes out under the name Maurice And The Beejays, and can be found on Spotify, Apple etc.

Due to the fact that, besides Barry, I haven’t got anybody else prepared to invest loads of unpaid time, I ended up playing most of the instruments and recorded myself as I was going. My wife Julia edited the artwork (after which I introduced a couple of typing errors) and our award-winning poet daughter Maya helped me with feedback on the lyrics.

The tracks were mastered by Ike Nossel, who has worked with a lot of names such as Def Leppard, George Martin, Gerry Rafferty, Hans Zimmer, Robin Trower, Jerry Marotta, Paul Young, Jack Bruce, and The Waterboys. Ike was also good friends with early Pink Floyd producer Norman Smith, whose son Nick ran Ike’s Parkgate Studio in East Sussex.

Would I play the album live?

That would be nice and there is nothing that I would like more, but somebody would have to stump up some money so that we could pay musicians who can play psychedelia to learn the material. Now there are very few gigs and every musician is after them, and psychedelia is a bit of a niche market. Maybe if we got offered a spot on TV, we could rope some people in.

Barry Jones jokingly said he wanted to go out and do a gig just featuring the spacey breakdowns in the middle of the songs, and we were in the process of searching for a guitarist who can play psychedelia before the lockdown. We remain open to offers!

But as for live music, it looks very bleak at the moment, but live music can never disappear completely. It is built into our DNA since somebody started dancing to the sound of somebody else banging two rocks together in a repeated pattern. I am positive though, having led the campaign to relax the laws governing the licensing of live music which resulted in the Live Music Act 2012, whenever people will be able to freely mix again it will be much easier for anyone to present live music virtually anywhere (between 8am and 11pm).

It’s a question of how many people can assemble safely and since music education in schools has almost disappeared completely since 2010, the ‘nationwide musicianship’ has begun to decrease significantly. How could it not? One thing the Government could do to resist the decline in UK Arts is to give the Arts the respect they deserve and re-introduce music education into the education system.

It’s going to be a long time before pubs will be able to operate at full capacity and the system only just manages to pay musicians in small venues. A lot of people are going to be under pressure to give up the idea of being professional musicians. Many will give up playing when there isn’t even an opportunity to perform, let alone get paid. That’s a really sad thing.

However, when you are bitten by the bug of music and just want to play – nothing will stop you. So, the diehards will keep going until the pandemic is over, even if they have to virtually starve. And it won’t help the small businesses which have closed, and all our hearts go out to the dedicated people who are losing their livelihoods.

However, it is to be hoped that with a greater appreciation and demand for live music from the public, many of these businesses will be able to start up again quickly when this nightmare is finally over and it is safe to do so.

Where I live in Hastings, there are a lot of really good musicians and the town is somewhat of a musical centre. In recent years, many more musicians have moved here so it is a bit like London with regard to competition for the number of gigs. In this situation, pay for bands drops, especially on gigs with free entry.

Since lockdown, music fans were so desperate for some live music, when outdoor events on Hastings Pier became possible again folk signalled that they were happy to pay a tip with a round of drinks or even an admission fee. Perhaps, in the future, audiences will need to pay something where previously, the live music was free.

In 2019, live music contributed £4.5 billion to the UK economy. This year, revenue has been almost zero since March and 2020 revenue will fall by 81% compared to 2019. In 2019, live music supported 210,000 FTEs (Full Time Equivalent), including 52,000 full-time, salaried roles. 50% of permanent roles will be lost by the end of the year (26,100 jobs), while temporary and freelance roles have already been decimated.

The UK Government could do well to observe what is happening in Australia due to the efforts of fellow live music campaigner John Wardle, who has had enormous success in rallying support for live music and focussing the attention of the Australian State Governments on assisting the hard-hit live music sector.

Through his decades of dedication John has enabled the Australian Government to appreciate the value of live and recorded music, not only to the economy but to the health of the Nation, and that is what we need more of in the UK. The Live Music Forum website is more of an archive these days, and we try to reflect a picture of what is currently happening on the Facebook page (address below). About ten years ago we introduced The Live Music Forum Copyright Campaign, to press for a wider distribution of copyright and this has its own Facebook page (address below).

And then there’s streaming!

The problems for recording artists started long before streaming and originally stemmed from the greed of the old major record companies who charged the earth for a penny’s worth of plastic and gave the artists next to nothing. Decades later we were paying over £10 for an album, so when the opportunity to download free copies of albums through Pirate Bay or Bit Torrent came, millions of people took up the option.

Previously, I have raised the point of low streaming rates paid to artists at a Westminster Media Forum, which gathers industry leaders and lawmakers to discuss the future of copyright and music in the UK. However, their focus seems to be rather more on protecting and maximising the digital rights of large companies that contribute to the economy. What they overlook is that we are all contributing to the economy.

So what does the future hold for Phil Little?

At the moment, I am undecided as to what style of music to pursue next. Recently, I acquired a mandolin and fancy having a go at a couple of tunes mixing that sound with an acoustic guitar and maybe even a violin, while avoiding a folk or country sound. It might go well with some Middle Eastern percussion, so I need to try it out.

I like Indian music, especially the drone sounds, and the first track I recorded for this project was very Indian but I kind of forgot or discounted it and it hasn’t been included. So, maybe I’ll do another psychedelic record with different sounds and influences. I quite enjoyed attempting to write a ‘song’.

However, my Samba and Afro-Cuban percussion tracks get the most streams, and rhythm is still the key to me. Then again, I have loads of unreleased trance tracks and I enjoy that techno side of it.

With work being so hard to get, prior to the lockdown I had just obtained all the gear I needed to go out and do a solo set mixing my techno tracks with live percussion. A while back a group of us tried this out at The Bay Hotel in Llanelli and the results were amazing. People were saying it was like being back in Ibiza and were phoning their friends to come down.

Earlier I mentioned The Live Music Forum Copyright Campaign and I am committed to pressing ahead with that. Lord Clement-Jones said to me in an email that if we wanted to get the interest of Westminster then we had to build a grassroots campaign, and that is proving to be slow going with the major problems that people have on their minds.

Mostly, I’d just like to keep playing and learning. In 2019, I completed fifty years of gigging and now feel extremely grateful to have had the opportunity to keep going so long as the music business has become harder and harder to survive in. What I wouldn’t give to be able to take the drumkit out, though!

Website: www.littledrum.co.uk

Facebook: www.facebook.com/PhilLittle4

Twitter: @phillittle

Live Music Forum FB: www.facebook.com/TheLiveMusicForum/

Copyright Campaign FB: www.facebook.com/LiveMusicForumCopyrightCampaign

…

Working Locally, Thinking Globally – MADCAP Global Commodities & Agri-business